In geometry, the area enclosed by a circle of radius r is πr2. Here the Greek letter π represents the constant ratio of the circumference of any circle to its diameter, approximately equal to 3.14159.

One method of deriving this formula, which originated with Archimedes, involves viewing the circle as the limit of a sequence of regular polygons. The area of a regular polygon is half its perimeter multiplied by the distance from its center to its sides, and the corresponding formula–that the area is half the perimeter times the radius–namely, A =

1

/

2

× 2πr × r, holds in the limit for a circle.

Although often referred to as the area of a circle in informal contexts, strictly speaking the term disk refers to the interior region of the circle, while circle is reserved for the boundary only, which is a curve and covers no area itself. Therefore, the area of a disk is the more precise phrase for the area enclosed by a circle.

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 Historical arguments

- 2.1 Using polygons

- 2.2 Archimedes's proof

- 2.2.1 Not greater

- 2.2.2 Not less

- 2.3 Rearrangement proof

- 3 Modern proofs

- 3.1 Onion proof

- 3.2 Triangle proof

- 3.3 Semicircle proof

- 4 Isoperimetric inequality

- 5 Fast approximation

- 5.1 Archimedes' doubling method

- 5.2 The Snell–Huygens refinement

- 5.3 Derivation of Archimedes' doubling formulae

- 6 Dart approximation

- 7 Finite rearrangement

- 8 Non-Euclidean circles

- 9 Generalizations

1 History

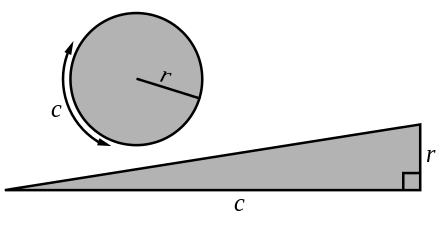

Modern mathematics can obtain the area using the methods of integral calculus or its more sophisticated offspring, real analysis. However, the area of a disk was studied by the Ancient Greeks. Eudoxus of Cnidus in the fifth century B.C. had found that the area of a disk is proportional to its radius squared.[1] Archimedes used the tools of Euclidean geometry to show that the area inside a circle is equal to that of a right triangle whose base has the length of the circle’s circumference and whose height equals the circle’s radius in his book Measurement of a Circle. The circumference is 2πr, and the area of a triangle is half the base times the height, yielding the area π r2 for the disk. Prior to Archimedes, Hippocrates of Chios was the first to show that the area of a disk is proportional to the square of its diameter, as part of his quadrature of the lune of Hippocrates,[2] but did not identify the constant of proportionality.

2 Historical arguments

A variety of arguments have been advanced historically to establish the equation {\displaystyle A=\pi r^{2}}{\displaystyle A=\pi r^{2}} to varying degrees of mathematical rigor. The most famous of these is Archimedes’ method of exhaustion, one of the earliest uses of the mathematical concept of a limit, as well as the origin of Archimedes’ axiom which remains part of the standard analytical treatment of the real number system. The original proof of Archimedes is not rigorous by modern standards, because it assumes that we can compare the length of arc of a circle to the length of a secant and a tangent line, and similar statements about the area, as geometrically evident.

2.1 Using polygons

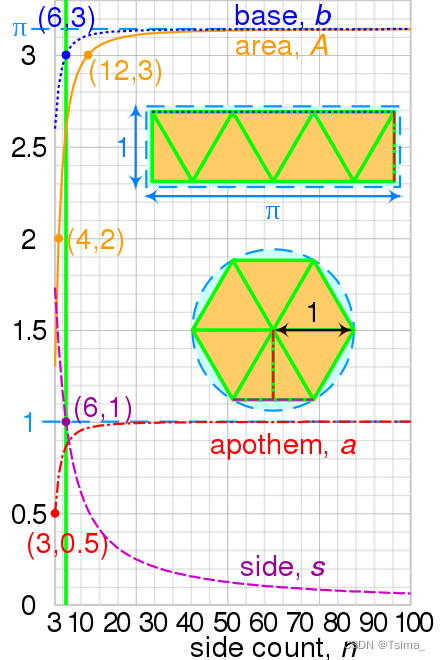

The area of a regular polygon is half its perimeter times the apothem. As the number of sides of the regular polygon increases, the polygon tends to a circle, and the apothem tends to the radius. This suggests that the area of a disk is half the circumference of its bounding circle times the radius.[3]

2.2 Archimedes’s proof

Following Archimedes’ argument in The Measurement of a Circle (c. 260 BCE), compare the area enclosed by a circle to a right triangle whose base has the length of the circle’s circumference and whose height equals the circle’s radius. If the area of the circle is not equal to that of the triangle, then it must be either greater or less. We eliminate each of these by contradiction, leaving equality as the only possibility. We use regular polygons in the same way.

2.2.1 Not greater

Suppose that the area C enclosed by the circle is greater than the area T = 1⁄2cr of the triangle. Let E denote the excess amount. Inscribe a square in the circle, so that its four corners lie on the circle. Between the square and the circle are four segments. If the total area of those gaps, G4, is greater than E, split each arc in half. This makes the inscribed square into an inscribed octagon, and produces eight segments with a smaller total gap, G8. Continue splitting until the total gap area, Gn, is less than E. Now the area of the inscribed polygon, Pn = C − Gn, must be greater than that of the triangle.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}E&{}=C-T\&{}>G_{n}\P_{n}&{}=C-G_{n}\&{}>C-E\P_{n}&{}>T\end{aligned}}}\begin{align}

E &{}= C - T \

&{}> G_n \

P_n &{}= C - G_n \

&{}> C - E \

P_n &{}> T

\end{align}

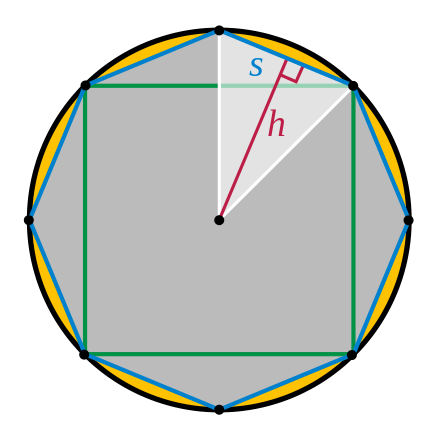

But this forces a contradiction, as follows. Draw a perpendicular from the center to the midpoint of a side of the polygon; its length, h, is less than the circle radius. Also, let each side of the polygon have length s; then the sum of the sides, ns, is less than the circle circumference. The polygon area consists of n equal triangles with height h and base s, thus equals 1⁄2nhs. But since h < r and ns < c, the polygon area must be less than the triangle area, 1⁄2cr, a contradiction. Therefore, our supposition that C might be greater than T must be wrong.

Circle with square and octagon inscribed, showing area gap

2.2.2 Not less

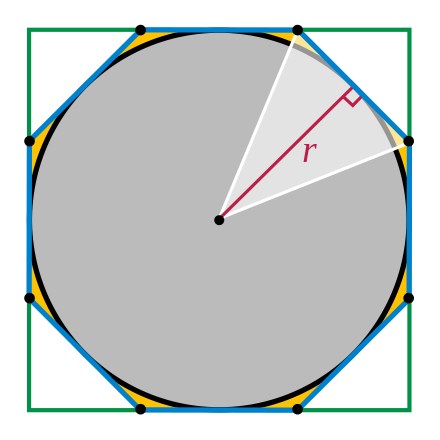

Suppose that the area enclosed by the circle is less than the area T of the triangle. Let D denote the deficit amount. Circumscribe a square, so that the midpoint of each edge lies on the circle. If the total area gap between the square and the circle, G4, is greater than D, slice off the corners with circle tangents to make a circumscribed octagon, and continue slicing until the gap area is less than D. The area of the polygon, Pn, must be less than T.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}D&{}=T-C\&{}>G_{n}\P_{n}&{}=C+G_{n}\&{}<C+D\P_{n}&{}<T\end{aligned}}}\begin{align}

D &{}= T - C \

&{}> G_n \

P_n &{}= C + G_n \

&{}< C + D \

P_n &{}< T

\end{align}

This, too, forces a contradiction. For, a perpendicular to the midpoint of each polygon side is a radius, of length r. And since the total side length is greater than the circumference, the polygon consists of n identical triangles with total area greater than T. Again we have a contradiction, so our supposition that C might be less than T must be wrong as well.

Therefore, it must be the case that the area enclosed by the circle is precisely the same as the area of the triangle. This concludes the proof.

Circle with square and octagon circumscribed, showing area gap

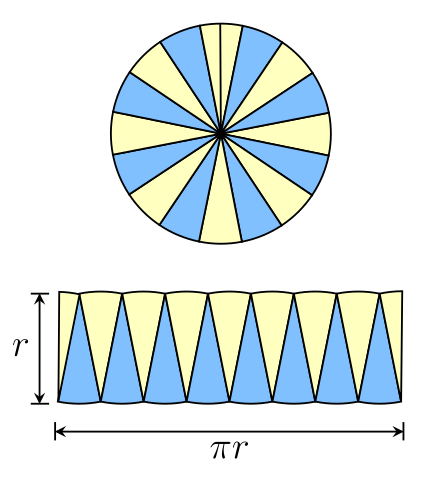

2.3 Rearrangement proof

Following Satō Moshun (Smith & Mikami 1914, pp. 130–132) and Leonardo da Vinci (Beckmann 1976, p. 19), we can use inscribed regular polygons in a different way. Suppose we inscribe a hexagon. Cut the hexagon into six triangles by splitting it from the center. Two opposite triangles both touch two common diameters; slide them along one so the radial edges are adjacent. They now form a parallelogram, with the hexagon sides making two opposite edges, one of which is the base, s. Two radial edges form slanted sides, and the height, h is equal to its apothem (as in the Archimedes proof). In fact, we can also assemble all the triangles into one big parallelogram by putting successive pairs next to each other. The same is true if we increase it to eight sides and so on. For a polygon with 2n sides, the parallelogram will have a base of length ns, and a height h. As the number of sides increases, the length of the parallelogram base approaches half the circle circumference, and its height approaches the circle radius. In the limit, the parallelogram becomes a rectangle with width πr and height r.

Unit disk area by rearranging n polygons.

polygon parallelogram

n side base height area

4 1.4142136 2.8284271 0.7071068 2.0000000

6 1.0000000 3.0000000 0.8660254 2.5980762

8 0.7653669 3.0614675 0.9238795 2.8284271

10 0.6180340 3.0901699 0.9510565 2.9389263

12 0.5176381 3.1058285 0.9659258 3.0000000

14 0.4450419 3.1152931 0.9749279 3.0371862

16 0.3901806 3.1214452 0.9807853 3.0614675

96 0.0654382 3.1410320 0.9994646 3.1393502

∞ 1/∞ π 1 π

Circle area by rearrangement

Graphs of side, s; apothem, a; and area, A of regular polygons of n sides and circumradius 1, with the base, b of a rectangle with the same area. The green line shows the case n = 6.

3 Modern proofs

There are various equivalent definitions of the constant π. The conventional definition in pre-calculus geometry is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter:

{\displaystyle \pi ={\frac {C}{D}}.}{\displaystyle \pi ={\frac {C}{D}}.}

However, because the circumference of a circle is not a primitive analytical concept, this definition is not suitable in modern rigorous treatments. A standard modern definition is that π is equal to twice the least positive root of the cosine function or, equivalently, the half-period of the sine (or cosine) function. The cosine function can be defined either as a power series, or as the solution of a certain differential equation. This avoids any reference to circles in the definition of π, so that statements about the relation of π to the circumference and area of circles are actually theorems, rather than definitions, that follow from the analytical definitions of concepts like “area” and “circumference”.

The analytical definitions are seen to be equivalent, if it is agreed that the circumference of the circle is measured as a rectifiable curve by means of the integral

{\displaystyle C=2\int _{-R}^{R}{\frac {R,dx}{\sqrt {R{2}-x{2}}}}=2R\int _{-1}^{1}{\frac {dx}{\sqrt {1-x^{2}}}}.}{\displaystyle C=2\int _{-R}^{R}{\frac {R,dx}{\sqrt {R{2}-x{2}}}}=2R\int _{-1}^{1}{\frac {dx}{\sqrt {1-x^{2}}}}.}

The integral appearing on the right is an abelian integral whose value is a half-period of the sine function, equal to π. Thus {\displaystyle C=2\pi R=\pi D}{\displaystyle C=2\pi R=\pi D} is seen to be true as a theorem.

Several of the arguments that follow use only concepts from elementary calculus to reproduce the formula {\displaystyle A=\pi r^{2}}{\displaystyle A=\pi r^{2}}, but in many cases to regard these as actual proofs, they rely implicitly on the fact that one can develop trigonometric functions and the fundamental constant π in a way that is totally independent of their relation to geometry. We have indicated where appropriate how each of these proofs can be made totally independent of all trigonometry, but in some cases that requires more sophisticated mathematical ideas than those afforded by elementary calculus.

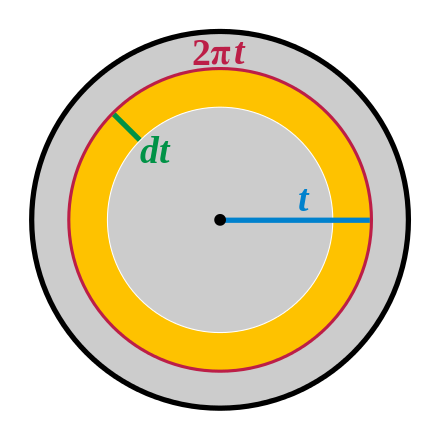

3.1 Onion proof

Using calculus, we can sum the area incrementally, partitioning the disk into thin concentric rings like the layers of an onion. This is the method of shell integration in two dimensions. For an infinitesimally thin ring of the “onion” of radius t, the accumulated area is 2πt dt, the circumferential length of the ring times its infinitesimal width (one can approximate this ring by a rectangle with width=2πt and height=dt). This gives an elementary integral for a disk of radius r.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} ®&{}=\int _{0}^{r}2\pi t,dt\&{}=2\pi \left[{\frac {t{2}}{2}}\right]_{0}{r}\&{}=\pi r^{2}.\end{aligned}}}{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} ®&{}=\int _{0}^{r}2\pi t,dt\&{}=2\pi \left[{\frac {t{2}}{2}}\right]_{0}{r}\&{}=\pi r^{2}.\end{aligned}}}

It is rigorously justified by the multivariate substitution rule in polar coordinates. Namely, the area is given by a double integral of the constant function 1 over the disk itself. If D denotes the disk, then the double integral can be computed in polar coordinates as follows:

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} ®&{}=\iint _{D}1\ d(x,y)\&{}=\iint _{D}t\ dt\ d\theta \&{}=\int _{0}^{r}\int _{0}^{2\pi }t\ d\theta \ dt\&{}=\int {0}^{r}\left[t\theta \right]{0}^{2\pi }dt\&{}=\int _{0}^{r}2\pi t,dt\\end{aligned}}}{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} ®&{}=\iint _{D}1\ d(x,y)\&{}=\iint _{D}t\ dt\ d\theta \&{}=\int _{0}^{r}\int _{0}^{2\pi }t\ d\theta \ dt\&{}=\int {0}^{r}\left[t\theta \right]{0}^{2\pi }dt\&{}=\int _{0}^{r}2\pi t,dt\\end{aligned}}}

which is the same result as obtained above.

An equivalent rigorous justification, without relying on the special coordinates of trigonometry, uses the coarea formula. Define a function {\displaystyle \rho :\mathbb {R} ^{2}\to \mathbb {R} }{\displaystyle \rho :\mathbb {R} ^{2}\to \mathbb {R} } by {\textstyle \rho (x,y)={\sqrt {x{2}+y{2}}}}{\textstyle \rho (x,y)={\sqrt {x{2}+y{2}}}}. Note ρ is a Lipschitz function whose gradient is a unit vector {\displaystyle |\nabla \rho |=1}{\displaystyle |\nabla \rho |=1} (almost everywhere). Let D be the disc {\displaystyle \rho <1}{\displaystyle \rho <1} in {\displaystyle \mathbb {R} ^{2}}\mathbb {R} ^{2}. We will show that {\displaystyle {\mathcal {L}}^{2}(D)=\pi }{\displaystyle {\mathcal {L}}^{2}(D)=\pi }, where {\displaystyle {\mathcal {L}}^{2}}{\displaystyle {\mathcal {L}}^{2}} is the two-dimensional Lebesgue measure in {\displaystyle \mathbb {R} ^{2}}\mathbb {R} ^{2}. We shall assume that the one-dimensional Hausdorff measure of the circle {\displaystyle \rho =r}{\displaystyle \rho =r} is {\displaystyle 2\pi r}2\pi r, the circumference of the circle of radius r. (This can be taken as the definition of circumference.) Then, by the coarea formula,

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\mathcal {L}}^{2}(D)&=\iint _{D}|\nabla \rho |,d{\mathcal {L}}^{2}\&=\int _{\mathbb {R} }{\mathcal {H}}^{1}(\rho ^{-1}®\cap D),dr\&=\int _{0}^{1}{\mathcal {H}}^{1}(\rho ^{-1}®),dr\&=\int _{0}^{1}2\pi r,dr=\pi .\end{aligned}}}{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\mathcal {L}}^{2}(D)&=\iint _{D}|\nabla \rho |,d{\mathcal {L}}^{2}\&=\int _{\mathbb {R} }{\mathcal {H}}^{1}(\rho ^{-1}®\cap D),dr\&=\int _{0}^{1}{\mathcal {H}}^{1}(\rho ^{-1}®),dr\&=\int _{0}^{1}2\pi r,dr=\pi .\end{aligned}}}

Area of the disk via ring integration

3.2 Triangle proof

Similar to the onion proof outlined above, we could exploit calculus in a different way in order to arrive at the formula for the area of a disk. Consider unwrapping the concentric circles to straight strips. This will form a right angled triangle with r as its height and 2πr (being the outer slice of onion) as its base.

Finding the area of this triangle will give the area of the disk

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\text{Area}}&{}={\frac {1}{2}}\cdot {\text{base}}\cdot {\text{height}}\&{}={\frac {1}{2}}\cdot 2\pi r\cdot r\&{}=\pi r^{2}\end{aligned}}}{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\text{Area}}&{}={\frac {1}{2}}\cdot {\text{base}}\cdot {\text{height}}\&{}={\frac {1}{2}}\cdot 2\pi r\cdot r\&{}=\pi r^{2}\end{aligned}}}

The opposite and adjacent angles for this triangle are respectively in degrees 9.0430611…, 80.956939… and in radians 0.1578311… OEIS: A233527, 1.4129651…OEIS: A233528.

Explicitly, we imagine dividing up a circle into triangles, each with a height equal to the circle’s radius and a base that is infinitesimally small. The area of each of these triangles is equal to {\displaystyle 1/2\cdot r\cdot du}{\displaystyle 1/2\cdot r\cdot du}. By summing up (integrating) all of the areas of these triangles, we arrive at the formula for the circle’s area:

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} ®&{}=\int {0}^{2\pi r}{\frac {1}{2}}r,du\&{}=\left[{\frac {1}{2}}ru\right]{0}^{2\pi r}\&{}=\pi r^{2}.\end{aligned}}}{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} ®&{}=\int {0}^{2\pi r}{\frac {1}{2}}r,du\&{}=\left[{\frac {1}{2}}ru\right]{0}^{2\pi r}\&{}=\pi r^{2}.\end{aligned}}}

It too can be justified by a double integral of the constant function 1 over the disk by reversing the order of integration and using a change of variables in the above iterated integral:

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} ®&{}=\iint _{D}1\ d(x,y)\&{}=\iint _{D}t\ dt\ d\theta \&{}=\int _{0}^{2\pi }\int _{0}^{r}t\ dt\ d\theta \&{}=\int _{0}^{2\pi }{\frac {1}{2}}r^{2}\ d\theta \\end{aligned}}}{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} ®&{}=\iint _{D}1\ d(x,y)\&{}=\iint _{D}t\ dt\ d\theta \&{}=\int _{0}^{2\pi }\int _{0}^{r}t\ dt\ d\theta \&{}=\int _{0}^{2\pi }{\frac {1}{2}}r^{2}\ d\theta \\end{aligned}}}

Making the substitution {\displaystyle u=r\theta ,\ du=r\ d\theta }{\displaystyle u=r\theta ,\ du=r\ d\theta } converts the integral to

{\displaystyle \int _{0}^{2\pi r}{\frac {1}{2}}{\frac {r^{2}}{r}}du=\int _{0}^{2\pi r}{\frac {1}{2}}r\ du}{\displaystyle \int _{0}^{2\pi r}{\frac {1}{2}}{\frac {r^{2}}{r}}du=\int _{0}^{2\pi r}{\frac {1}{2}}r\ du}

which is the same as the above result.

The triangle proof can be reformulated as an application of Green’s theorem in flux-divergence form (i.e. a two-dimensional version of the divergence theorem), in a way that avoids all mention of trigonometry and the constant π. Consider the vector field {\displaystyle \mathbf {r} =x\mathbf {i} +y\mathbf {j} }{\displaystyle \mathbf {r} =x\mathbf {i} +y\mathbf {j} } in the plane. So the divergence of r is equal to two, and hence the area of a disc D is equal to

{\displaystyle A={\frac {1}{2}}\iint _{D}\operatorname {div} \mathbf {r} ,dA.}{\displaystyle A={\frac {1}{2}}\iint _{D}\operatorname {div} \mathbf {r} ,dA.}

By Green’s theorem, this is the same as the outward flux of r across the circle bounding D:

{\displaystyle A={\frac {1}{2}}\oint _{\partial D}\mathbf {r} \cdot \mathbf {n} ,ds}{\displaystyle A={\frac {1}{2}}\oint _{\partial D}\mathbf {r} \cdot \mathbf {n} ,ds}

where n is the unit normal and ds is the arc length measure. For a circle of radius R centered at the origin, we have {\displaystyle |\mathbf {r} |=R}{\displaystyle |\mathbf {r} |=R} and {\displaystyle \mathbf {n} =\mathbf {r} /R}{\displaystyle \mathbf {n} =\mathbf {r} /R}, so the above equality is

{\displaystyle A={\frac {1}{2}}\oint _{\partial D}\mathbf {r} \cdot {\frac {\mathbf {r} }{R}},ds={\frac {R}{2}}\oint _{\partial D},ds.}{\displaystyle A={\frac {1}{2}}\oint _{\partial D}\mathbf {r} \cdot {\frac {\mathbf {r} }{R}},ds={\frac {R}{2}}\oint _{\partial D},ds.}

The integral of ds over the whole circle {\displaystyle \partial D}\partial D is just the arc length, which is its circumference, so this shows that the area A enclosed by the circle is equal to {\displaystyle R/2}R/2 times the circumference of the circle.

Another proof that uses triangles considers the area enclosed by a circle to be made up of an infinite number of triangles (i.e. the triangles each have an angle of d𝜃 at the centre of the circle), each with an area of

1

/

2

· r2 · d𝜃 (derived from the expression for the area of a triangle:

1

/

2

· a · b · sin𝜃 =

1

/

2

· r · r · sin(d𝜃) =

1

/

2

· r2 · d𝜃). Note that sin(d𝜃) ≈ d𝜃 due to small angle approximation. Through summing the areas of the triangles, the expression for the area of the circle can therefore be found:

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} &{}=\int {0}^{2\pi }{\frac {1}{2}}r^{2},d\theta \&{}=\left[{\frac {1}{2}}r^{2}\theta \right]{0}^{2\pi }\&{}=\pi r^{2}.\end{aligned}}}{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathrm {Area} &{}=\int {0}^{2\pi }{\frac {1}{2}}r^{2},d\theta \&{}=\left[{\frac {1}{2}}r^{2}\theta \right]{0}^{2\pi }\&{}=\pi r^{2}.\end{aligned}}}

The circle and the triangle are equal in area.

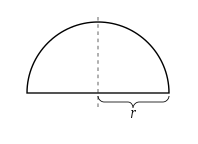

3.3 Semicircle proof

Note that the area of a semicircle of radius r can be computed by the integral {\textstyle \int _{-r}^{r}{\sqrt {r{2}-x{2}}},dx}{\textstyle \int _{-r}^{r}{\sqrt {r{2}-x{2}}},dx}.

By trigonometric substitution, we substitute {\displaystyle x=r\sin \theta }x=r\sin \theta , hence {\displaystyle dx=r\cos \theta ,d\theta .}{\displaystyle dx=r\cos \theta ,d\theta .}

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int _{-r}^{r}{\sqrt {r{2}-x{2}}},dx&=\int _{-{\frac {\pi }{2}}}^{\frac {\pi }{2}}{\sqrt {r^{2}\left(1-\sin ^{2}\theta \right)}}\cdot r\cos \theta ,d\theta \&=2r^{2}\int _{0}^{\frac {\pi }{2}}\cos ^{2}\theta ,d\theta \&={\frac {\pi r^{2}}{2}}.\end{aligned}}}{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\int _{-r}^{r}{\sqrt {r{2}-x{2}}},dx&=\int _{-{\frac {\pi }{2}}}^{\frac {\pi }{2}}{\sqrt {r^{2}\left(1-\sin ^{2}\theta \right)}}\cdot r\cos \theta ,d\theta \&=2r^{2}\int _{0}^{\frac {\pi }{2}}\cos ^{2}\theta ,d\theta \&={\frac {\pi r^{2}}{2}}.\end{aligned}}}

The last step follows since the trigonometric identity {\displaystyle \cos(\theta )=\sin(\pi /2-\theta )}{\displaystyle \cos(\theta )=\sin(\pi /2-\theta )} implies that {\displaystyle \cos ^{2}\theta }\cos ^{2}\theta and {\displaystyle \sin ^{2}\theta }{\displaystyle \sin ^{2}\theta } have equal integrals over the interval {\displaystyle [0,\pi /2]}[0,\pi /2], using integration by substitution. But on the other hand, since {\displaystyle \cos ^{2}\theta +\sin ^{2}\theta =1}{\displaystyle \cos ^{2}\theta +\sin ^{2}\theta =1}, the sum of the two integrals is the length of that interval, which is {\displaystyle \pi /2}\pi /2. Consequently, the integral of {\displaystyle \cos ^{2}\theta }\cos ^{2}\theta is equal to half the length of that interval, which is {\displaystyle \pi /4}\pi /4.

Therefore, the area of a circle of radius r, which is twice the area of the semi-circle, is equal to {\displaystyle 2\cdot {\frac {\pi r^{2}}{2}}=\pi r^{2}}2\cdot {\frac {\pi r^{2}}{2}}=\pi r^{2}.

This particular proof may appear to beg the question, if the sine and cosine functions involved in the trigonometric substitution are regarded as being defined in relation to circles. However, as noted earlier, it is possible to define sine, cosine, and π in a way that is totally independent of trigonometry, in which case the proof is valid by the change of variables formula and Fubini’s theorem, assuming the basic properties of sine and cosine (which can also be proved without assuming anything about their relation to circles).

A semicircle of radius r

4 Isoperimetric inequality

The circle is the closed curve of least perimeter that encloses the maximum area. This is known as the isoperimetric inequality, which states that if a rectifiable Jordan curve in the Euclidean plane has perimeter C and encloses an area A (by the Jordan curve theorem) then

{\displaystyle 4\pi A\leq C^{2}.}{\displaystyle 4\pi A\leq C^{2}.}

Moreover, equality holds in this inequality if and only if the curve is a circle, in which case {\displaystyle A=\pi r^{2}}{\displaystyle A=\pi r^{2}} and {\displaystyle C=2\pi r}{\displaystyle C=2\pi r}.

5 Fast approximation

The calculations Archimedes used to approximate the area numerically were laborious, and he stopped with a polygon of 96 sides. A faster method uses ideas of Willebrord Snell (Cyclometricus, 1621), further developed by Christiaan Huygens (De Circuli Magnitudine Inventa, 1654), described in Gerretsen & Verdenduin (1983, pp. 243–250).

5.1 Archimedes’ doubling method

Given a circle, let un be the perimeter of an inscribed regular n-gon, and let Un be the perimeter of a circumscribed regular n-gon. Then un and Un are lower and upper bounds for the circumference of the circle that become sharper and sharper as n increases, and their average (un + Un)/2 is an especially good approximation to the circumference. To compute un and Un for large n, Archimedes derived the following doubling formulae:

{\displaystyle u_{2n}={\sqrt {U_{2n}u_{n}}}}u_{2n} = \sqrt{U_{2n} u_{n}} (geometric mean), and

{\displaystyle U_{2n}={\frac {2U_{n}u_{n}}{U_{n}+u_{n}}}}U_{2n} = \frac{2 U_{n} u_{n}}{ U_{n} + u_{n}} (harmonic mean).

Starting from a hexagon, Archimedes doubled n four times to get a 96-gon, which gave him a good approximation to the circumference of the circle.

In modern notation, we can reproduce his computation (and go further) as follows. For a unit circle, an inscribed hexagon has u6 = 6, and a circumscribed hexagon has U6 = 4√3. Doubling seven times yields

Archimedes doubling seven times; n = 6×2k.

k n un Un

un + Un

/

4

0 6 6.0000000 6.9282032 3.2320508

1 12 6.2116571 6.4307806 3.1606094

2 24 6.2652572 6.3193199 3.1461443

3 48 6.2787004 6.2921724 3.1427182

4 96 6.2820639 6.2854292 3.1418733

5 192 6.2829049 6.2837461 3.1416628

6 384 6.2831152 6.2833255 3.1416102

7 768 6.2831678 6.2832204 3.1415970

(Here

un + Un

/

2

approximates the circumference of the unit circle, which is 2π, so

un + Un

/

4

approximates π.)

The last entry of the table has 355⁄113 as one of its best rational approximations; i.e., there is no better approximation among rational numbers with denominator up to 113. The number 355⁄113 is also an excellent approximation to π, better than any other rational number with denominator less than 16604.[4]

5.2 The Snell–Huygens refinement

Snell proposed (and Huygens proved) a tighter bound than Archimedes’:

{\displaystyle n{\frac {3\sin {\frac {\pi }{n}}}{2+\cos {\frac {\pi }{n}}}}<\pi <n\left(2\sin {\frac {\pi }{3n}}+\tan {\frac {\pi }{3n}}\right).}{\displaystyle n{\frac {3\sin {\frac {\pi }{n}}}{2+\cos {\frac {\pi }{n}}}}<\pi <n\left(2\sin {\frac {\pi }{3n}}+\tan {\frac {\pi }{3n}}\right).}

This for n = 48 gives a better approximation (about 3.14159292) than Archimedes’ method for n = 768.

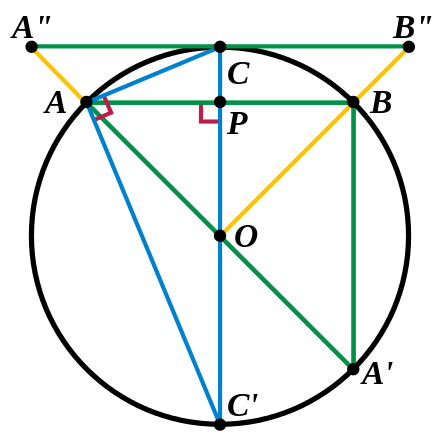

5.3 Derivation of Archimedes’ doubling formulae

Let one side of an inscribed regular n-gon have length sn and touch the circle at points A and B. Let A′ be the point opposite A on the circle, so that A′A is a diameter, and A′AB is an inscribed triangle on a diameter. By Thales’ theorem, this is a right triangle with right angle at B. Let the length of A′B be cn, which we call the complement of sn; thus cn2+sn2 = (2r)2. Let C bisect the arc from A to B, and let C′ be the point opposite C on the circle. Thus the length of CA is s2n, the length of C′A is c2n, and C′CA is itself a right triangle on diameter C′C. Because C bisects the arc from A to B, C′C perpendicularly bisects the chord from A to B, say at P. Triangle C′AP is thus a right triangle, and is similar to C′CA since they share the angle at C′. Thus all three corresponding sides are in the same proportion; in particular, we have C′A : C′C = C′P : C′A and AP : C′A = CA : C′C. The center of the circle, O, bisects A′A, so we also have triangle OAP similar to A′AB, with OP half the length of A′B. In terms of side lengths, this gives us

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}c_{2n}^{2}&{}=\left(r+{\frac {1}{2}}c_{n}\right)2r\c_{2n}&{}={\frac {s_{n}}{s_{2n}}}.\end{aligned}}}\begin{align}

c_{2n}^2 &{}= \left( r + \frac{1}{2} c_n \right) 2r \

c_{2n} &{}= \frac{s_n}{s_{2n}} .

\end{align}

In the first equation C′P is C′O+OP, length r+1⁄2cn, and C′C is the diameter, 2r. For a unit circle we have the famous doubling equation of Ludolph van Ceulen,

{\displaystyle c_{2n}={\sqrt {2+c_{n}}}.}{\displaystyle c_{2n}={\sqrt {2+c_{n}}}.}

If we now circumscribe a regular n-gon, with side A″B″ parallel to AB, then OAB and OA″B″ are similar triangles, with A″B″ : AB = OC : OP. Call the circumscribed side Sn; then this is Sn : sn = 1 : 1⁄2cn. (We have again used that OP is half the length of A′B.) Thus we obtain

{\displaystyle c_{n}=2{\frac {s_{n}}{S_{n}}}.}{\displaystyle c_{n}=2{\frac {s_{n}}{S_{n}}}.}

Call the inscribed perimeter un = nsn, and the circumscribed perimeter Un = nSn. Then combining equations, we have

{\displaystyle c_{2n}={\frac {s_{n}}{s_{2n}}}=2{\frac {s_{2n}}{S_{2n}}},} c_{2n} = \frac{s_n}{s_{2n}} = 2 \frac{s_{2n}}{S_{2n}} ,

so that

{\displaystyle u_{2n}^{2}=u_{n}U_{2n}.}{\displaystyle u_{2n}^{2}=u_{n}U_{2n}.}

This gives a geometric mean equation.

We can also deduce

{\displaystyle 2{\frac {s_{2n}}{S_{2n}}}{\frac {s_{n}}{s_{2n}}}=2+2{\frac {s_{n}}{S_{n}}},} 2 \frac{s_{2n}}{S_{2n}} \frac{s_n}{s_{2n}} = 2 + 2 \frac{s_n}{S_n} ,

or

{\displaystyle {\frac {2}{U_{2n}}}={\frac {1}{u_{n}}}+{\frac {1}{U_{n}}}.} \frac{2}{U_{2n}} = \frac{1}{u_n} + \frac{1}{U_n} .

This gives a harmonic mean equation.

Circle with similar triangles: circumscribed side, inscribed side and complement, inscribed split side and complement

6 Dart approximation

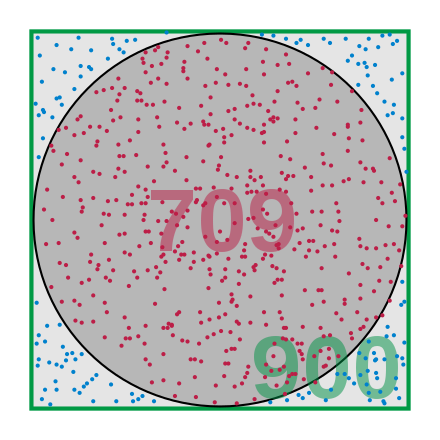

When more efficient methods of finding areas are not available, we can resort to “throwing darts”. This Monte Carlo method uses the fact that if random samples are taken uniformly scattered across the surface of a square in which a disk resides, the proportion of samples that hit the disk approximates the ratio of the area of the disk to the area of the square. This should be considered a method of last resort for computing the area of a disk (or any shape), as it requires an enormous number of samples to get useful accuracy; an estimate good to 10−n requires about 100n random samples (Thijssen 2006, p. 273).

Unit circle area Monte Carlo integration. Estimate by these 900 samples is 4×

709

/

900

= 3.15111…

7 Finite rearrangement

We have seen that by partitioning the disk into an infinite number of pieces we can reassemble the pieces into a rectangle. A remarkable fact discovered relatively recently (Laczkovich 1990) is that we can dissect the disk into a large but finite number of pieces and then reassemble the pieces into a square of equal area. This is called Tarski’s circle-squaring problem. The nature of Laczkovich’s proof is such that it proves the existence of such a partition (in fact, of many such partitions) but does not exhibit any particular partition.

8 Non-Euclidean circles

Circles can be defined in non-Euclidean geometry, and in particular in the hyperbolic and elliptic planes.

For example, the unit sphere {\displaystyle S^{2}(1)}{\displaystyle S^{2}(1)} is a model for the two-dimensional elliptic plane. It carries an intrinsic metric that arises by measuring geodesic length. The geodesic circles are the parallels in a geodesic coordinate system.

More precisely, fix a point {\displaystyle \mathbf {z} \in S^{2}(1)}{\displaystyle \mathbf {z} \in S^{2}(1)} that we place at the zenith. Associated to that zenith is a geodesic polar coordinate system {\displaystyle (\phi ,\theta )}{\displaystyle (\phi ,\theta )}, {\displaystyle 0\leq \phi \leq \pi }{\displaystyle 0\leq \phi \leq \pi }, {\displaystyle 0\leq \theta <2\pi }{\displaystyle 0\leq \theta <2\pi }, where z is the point {\displaystyle \phi =0}\phi =0. In these coordinates, the geodesic distance from z to any other point {\displaystyle \mathbf {x} \in S^{2}(1)}{\displaystyle \mathbf {x} \in S^{2}(1)} having coordinates {\displaystyle (\phi ,\theta )}{\displaystyle (\phi ,\theta )} is the value of {\displaystyle \phi }\phi at x. A spherical circle is the set of points a geodesic distance R from the zenith point z. Equivalently, with a fixed embedding into {\displaystyle \mathbb {R} ^{3}}\mathbb {R} ^{3}, the spherical circle of radius {\displaystyle R\leq \pi }{\displaystyle R\leq \pi } centered at z is the set of x in {\displaystyle S^{2}(1)}{\displaystyle S^{2}(1)} such that {\displaystyle \mathbf {x} \cdot \mathbf {z} =\cos R}{\displaystyle \mathbf {x} \cdot \mathbf {z} =\cos R}.

We can also measure the area of the spherical disk enclosed within a spherical circle, using the intrinsic surface area measure on the sphere. The area of the disk of radius R is then given by

{\displaystyle A=\int _{0}^{2\pi }\int _{0}^{R}\sin(\phi )d\phi ,d\theta =2\pi (1-\cos R).}{\displaystyle A=\int _{0}^{2\pi }\int _{0}^{R}\sin(\phi )d\phi ,d\theta =2\pi (1-\cos R).}

More generally, if a sphere {\displaystyle S^{2}(\rho )}{\displaystyle S^{2}(\rho )} has radius of curvature {\displaystyle \rho }\rho , then the area of the disk of radius R is given by

{\displaystyle A=2\pi \rho ^{2}(1-\cos(R/\rho )).}{\displaystyle A=2\pi \rho ^{2}(1-\cos(R/\rho )).}

Observe that, as an application of L’Hôpital’s rule, this tends to the Euclidean area {\displaystyle \pi R^{2}}\pi R^2 in the flat limit {\displaystyle \rho \to \infty }{\displaystyle \rho \to \infty }.

The hyperbolic case is similar, with the area of a disk of intrinsic radius R in the (constant curvature {\displaystyle -1}-1) hyperbolic plane given by

{\displaystyle A=2\pi (1-\cosh R)}{\displaystyle A=2\pi (1-\cosh R)}

where cosh is the hyperbolic cosine. More generally, for the constant curvature {\displaystyle -k}-k hyperbolic plane, the answer is

{\displaystyle A=2\pi k^{-2}(1-\cosh(kR)).}{\displaystyle A=2\pi k^{-2}(1-\cosh(kR)).}

These identities are important for comparison inequalities in geometry. For example, the area enclosed by a circle of radius R in a flat space is always greater than the area of a spherical circle and smaller than a hyperbolic circle, provided all three circles have the same (intrinsic) radius. That is,

{\displaystyle 2\pi (1-\cos R)<\pi R^{2}<2\pi (1-\cosh R)}{\displaystyle 2\pi (1-\cos R)<\pi R^{2}<2\pi (1-\cosh R)}

for all {\displaystyle R>0}R>0. Intuitively, this is because the sphere tends to curve back on itself, yielding circles of smaller area than those in the plane, whilst the hyperbolic plane, when immersed into space, develops fringes that produce additional area. It is more generally true that the area of the circle of a fixed radius R is a strictly decreasing function of the curvature.

In all cases, if {\displaystyle k}k is the curvature (constant, positive or negative), then the isoperimetric inequality for a domain with area A and perimeter L is

{\displaystyle L^{2}\geq 4\pi A-kA^{2}}{\displaystyle L^{2}\geq 4\pi A-kA^{2}}

where equality is achieved precisely for the circle.[5]

9 Generalizations

We can stretch a disk to form an ellipse. Because this stretch is a linear transformation of the plane, it has a distortion factor which will change the area but preserve ratios of areas. This observation can be used to compute the area of an arbitrary ellipse from the area of a unit circle.

Consider the unit circle circumscribed by a square of side length 2. The transformation sends the circle to an ellipse by stretching or shrinking the horizontal and vertical diameters to the major and minor axes of the ellipse. The square gets sent to a rectangle circumscribing the ellipse. The ratio of the area of the circle to the square is π/4, which means the ratio of the ellipse to the rectangle is also π/4. Suppose a and b are the lengths of the major and minor axes of the ellipse. Since the area of the rectangle is ab, the area of the ellipse is πab/4.

We can also consider analogous measurements in higher dimensions. For example, we may wish to find the volume inside a sphere. When we have a formula for the surface area, we can use the same kind of “onion” approach we used for the disk.